When I hear ‘accessibility’, I think of wheelchair ramps, braille subtexts, and the described video message before TV shows as a kid. However, Charlie Watson’s talk at UVic about digital accessibility and assistive technology made me realise how widespread – and vital – accessibility is.

Watson, who oversees the Adaptive Technology Program at UVic’s Centre for Accessible Learning, covered everything from high-tech gadgets like braille displays to minor yet significant adjustments we may make in a Word document or a Zoom chat in his informative presentation.

Watson’s criticism of the phrases adaptive and assistive technology was the first thing that caught my attention. In reality, these tools are part of a continuum, but we frequently isolate “special” technology for individuals with disabilities from the tools that everyone uses, such as screen magnifiers or voice dictation. Consider using automated subtitles in a noisy café or text-to-speech while driving. Everyone benefits from accessibility, or put so bluntly by Watson: “Ability is temporary. You will be disabled one day. Design for that now.”

We need to stop expecting people to change to fit our systems. We need to design systems that fit people. Whether that’s ensuring captions are accurate, documents are screen-reader friendly, or diagrams aren’t cluttered and color-dependent, small changes go a long way. As someone who never thought twice about hyperlink text, I now cringe when I see “Click here.” Charlie’s point about screen reader users encountering a wall of meaningless links hit hard: access starts with intentional design.

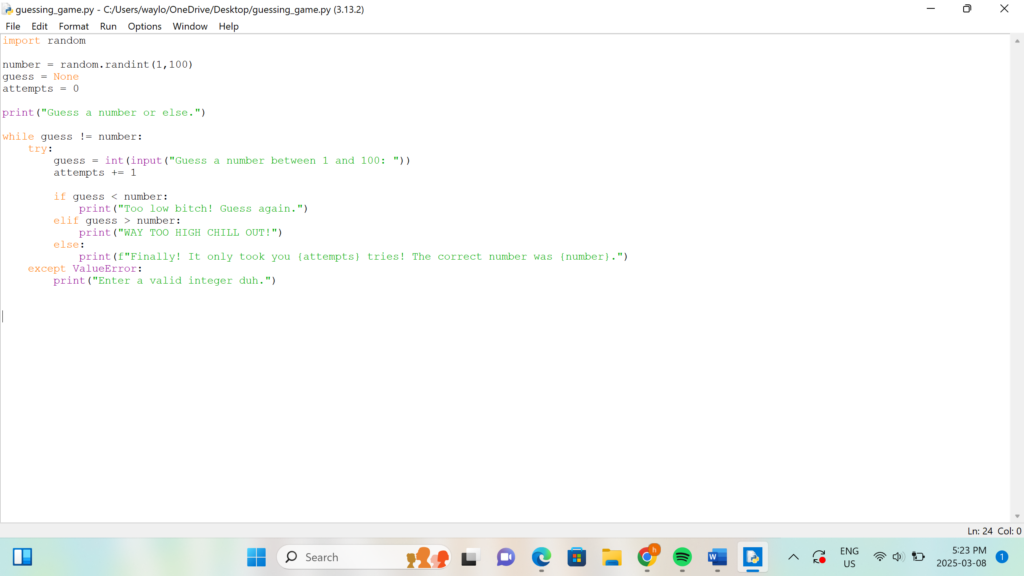

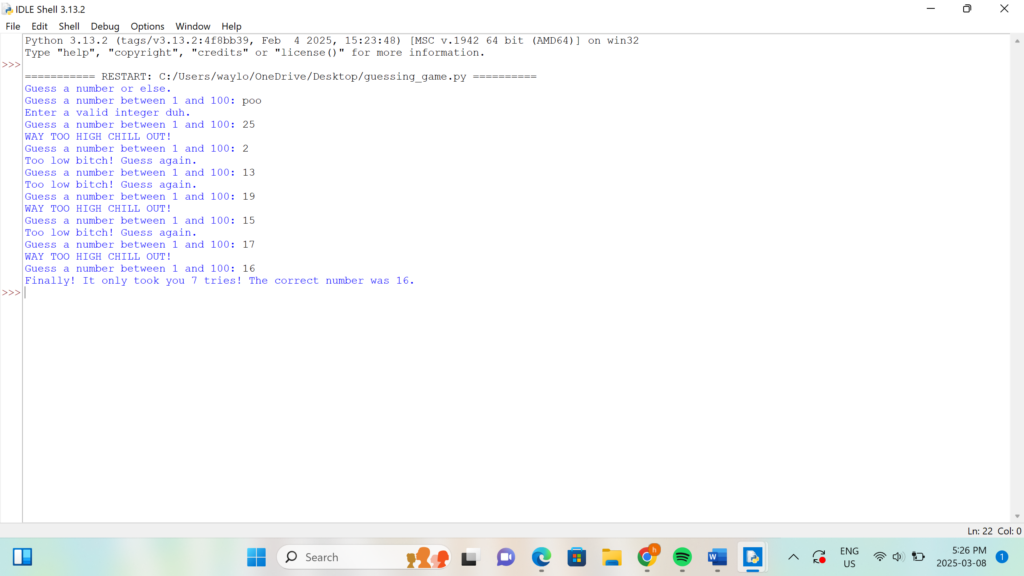

It was impressive how many options were showcased, ranging from dictation software and other keyboards to immersive reading modes and haptic visuals. The fact that so many are already included in devices or are publicly accessible, such as Otter.ai for transcriptions or Microsoft Edge’s Immersive Reader, was even more startling. Access isn’t always the problem; awareness is.

Charlie also reminded us that innovation doesn’t have to be costly by bringing up the community-built 3D printed technology. It can be open-source, creative, and cooperative.

Charlie’s presentation was a call-in rather than merely a how-to. A reminder that charity is not the same as accessibility. It’s fairness. The “selfish” reason to care is that accessible design benefits everyone, including the exhausted reader, the ageing professor, the parent with a sleeping infant, and the overworked student. When the digital world shifts towards equity and usability, we all gain.