Annotation to me has always been something quite specific and concerted; when I think of annotation, I of think sticky notes in textbooks, comments on Google Docs, and dreaded English assignments. Dr. Remi Kalir, however, asserts that annotation is a social, political, and widely encompassing practice, influencing how we interact with the outside world, reaching far beyond a study technique. If you think about, this blog post is in a sense an annotation, and any thoughts or comments that I might provoke from you here would be annotations as well.

The complex, multi-layered realm of social annotation—how we read and write together, why it matters, and what it tells about power, learning, and community—was recently explored by Dr. Kalir in a discussion led by Dr. Valerie Irvine.

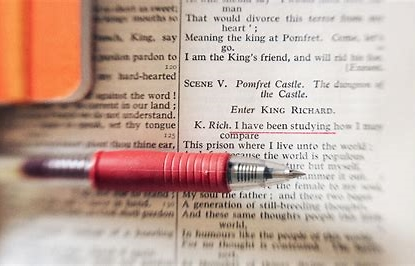

At its core, annotation is simple: it’s a note added to a text. But Kalir urges us to see annotation as a literacy practice—a way to not just understand texts, but also to engage critically with the world around us. From sticky notes on recipes to projected messages on protest walls, annotation is everywhere. It’s how we clarify, contest, question, and connect.

Social annotation depthens this concept with collaboration. It invites people to comment, question, and co-create meaning by putting them in the margins. Digital annotations made possible by tools like Hypothesis can be shared publicly with the world or privately with a class.

Social annotation isn’t simply about technology; it’s about education. It gives teachers new avenues for instruction and interaction. Consider starting a lesson by asking students to annotate the syllabus together, marking questions, offering feedback on rules, and helping to create the classroom atmosphere. It is reflective, democratic, and participatory.

Kalir’s work also emphasizes that annotation, like many aspects of literacy, is something powerful. From stop signs modified to acknowledge Indigenous lands to projected images on monuments during racial justice protests, annotation can be a way to challenge dominant systems and reimagine social realities.

In his forthcoming book Re/Marks on Power, Kalir explores how annotation is intertwined with political discourse. The act of “adding a note” becomes a form of resistance and reclamation.

Annotation isn’t just for academics; it’s for anyone who can read, write, observe, reflect; it’s for anyone that can form original thoughts. Whether you’re jotting down thoughts in a book, leaving a sticky note on the fridge, or using digital tools to respond to a peer’s blog post, you’re participating in a practice that’s as old as writing itself.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.